Look at a map of Seaside and a story starts to form. At its center, Cal State Monterey Bay (CSUMB), a modern campus still intimately connected to its military past, where a shared experience among many students remains in the reused military barracks they live in during their freshman year.

Not far west from CSUMB, rows of decrepit barracks are still in the process of being torn down, remnants of Fort Ord not lucky enough to be reused. Go east, and an old sign and a series of dead-end roundabouts mark the now mostly defunct University of California Monterey Bay Education, Science, and Technology Center (UC MBEST).

North, the Monterey Institute for Research in Astronomy (MIRA) sits active but odd and out of place in the corner of a vast expanse of concrete, while in the south buildings still bear their original building numbers from when Fort Ord was active.

There is a tension here, an indecision between past and future. Seventy-year-old derelicts standing alongside brand-new developments, one that only now is beginning to be resolved as Seaside grows.

At CSUMB, one building lies at the epicenter of this tension. Small, unassuming, with a weather-beaten porch, flecking roof and a rust-covered mailbox. Labeled building 491 on campus maps, the Oaks Hall Annex sits tucked behind Oaks Hall, barely visible from the street. It is largely a forgotten building, its name or existence not even mentioned on a campus plan from 2007.

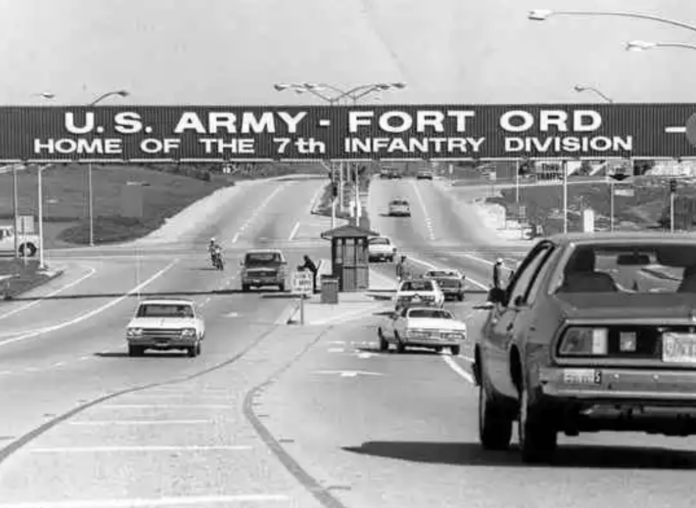

Building 491’s story begins with Fort Ord, which officially closed in 1994, after the passing of the 1988 Base Closure and Relocation Act. Intended to shutter or reallocate defunct military installations, Fort Ord would be first on the chopping block. Only a year later in 1995, CSUMB would hold its first classes on the old base.

When Fort Ord was in its prime it had over 600 buildings stretching from 8th Avenue to the coast. Where there is now a Veteran’s Association Clinic, a shopping center and vast expanses of dirt once lay something akin to a bustling city, one complete with dentist’s offices, theaters, hospitals, chapels and housing for the legions of soldiers stationed there.

In contrast, CSUMB appears to be only a shadow of the vast complex which used to exist. Although many buildings from Fort Ord were originally earmarked for rehabilitation, founding faculty member Qun Wang recalls they discovered it was “cheaper to tear them down.”

Barracks, maintenance shops and classrooms were ripped out to clear space for the growing college. CSUMB’s Master Plan discusses the process of removal, “The university has been able to reuse 66 military buildings… to date, a substantial amount of time and resources have been spent removing approximately 274 derelict structures on campus, the last of which are currently being demolished.”

In this context, it’s remarkable that Building 491 survived at all. It is not a permanent concrete construction like many of the buildings still in use by CSUMB, nor does it hold some obvious secondary function like the Meeting House.

Maps stored at the Chamberlin Military Library show 491 was put up sometime between 1978 and 1982 for use by the 127th Signal Battalion. On these maps, it is labeled T-4804, the T standing for temporary. Its recent construction compared to the rest of Fort Ord, most of which was built in the 1940s in response to World War II, saved it from the rot which doomed much of the old fort to destruction.

But 491 might have been torn down anyway if not for another lucky break. Maps show 491 was originally one of four identical buildings, labeled T-4801-4803. Those are gone now, but the lot’s unusual crescent shape curves just enough to avoid the building’s footprint.

In its current form, 491 is a look into a past slowly being forgotten. As Seaside and Marina expand into the future, much of the history of Fort Ord is becoming buried under new growth, only visible through photos and archival documents.

But its story doesn’t end in the past. To discover how it lasted into the modern day requires a look into the Fort Ord Reuse Authority (FORA) and their dream of a new Silicon Valley in the heart of Monterey Bay, read part two in next week’s edition.